Download the PDF of this Slide Set here.

How to Grow Resilient Well-Being In Your Brain and Your Life (SLIDES)

How to Grow Resilient Well-Being

In Your Brain and Your Life

Greater Good Science Center, UC Berkeley

December 4, 2018 | Rick Hanson, Ph.D.

1

The Value of Inner Resources

To deal with challenges and have lasting well-being in a changing world, we’ve got to be resilient.

To be resilient, we’ve got to have inner strengths.

2

In one word, what is an inner strength you use to deal with your challenges?

3

Some Inner Resources

Mindfulness

Patience, Determination, Grit

Emotional Intelligence

Character Virtues

Positive Emotions

Interpersonal Skills

4

The harder a person’s life, the more challenges one has, the less the outer world is helping – the more important it is to develop inner strengths.

5

The majority of our inner resources are acquired, through emotional, somatic, social, and motivational learning – which is fundamentally hopeful.

6

Which means Changing the Brain for the Better

7

Self-Directed Neuroplasticity

8

8

Inner strengths are acquired

in two stages:

Encoding → Consolidation

Activation → Installation

State → Trait

9

We become more compassionate by repeatedly installing experiences of compassion.

We become more grateful by repeatedly installing experiences of gratitude.

We become more mindful by repeatedly installing experiences of mindfulness.

10

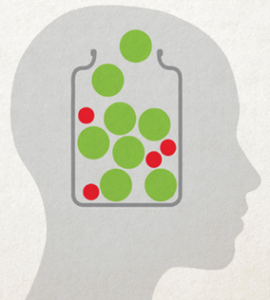

BUT: Experiencing doesn’t equal learning. Activation without installation may be pleasant, but no trait resources are acquired.

What fraction of our beneficial mental states lead to lasting changes in neural structure or function?

11

In one word, how many times a day do you slow down to help a good experience sink into you?

12

People focus more on activation than on installation.

This reduces the gains from mindfulness programs, human resources training, coaching, psychotherapy, and self-help activities.

13

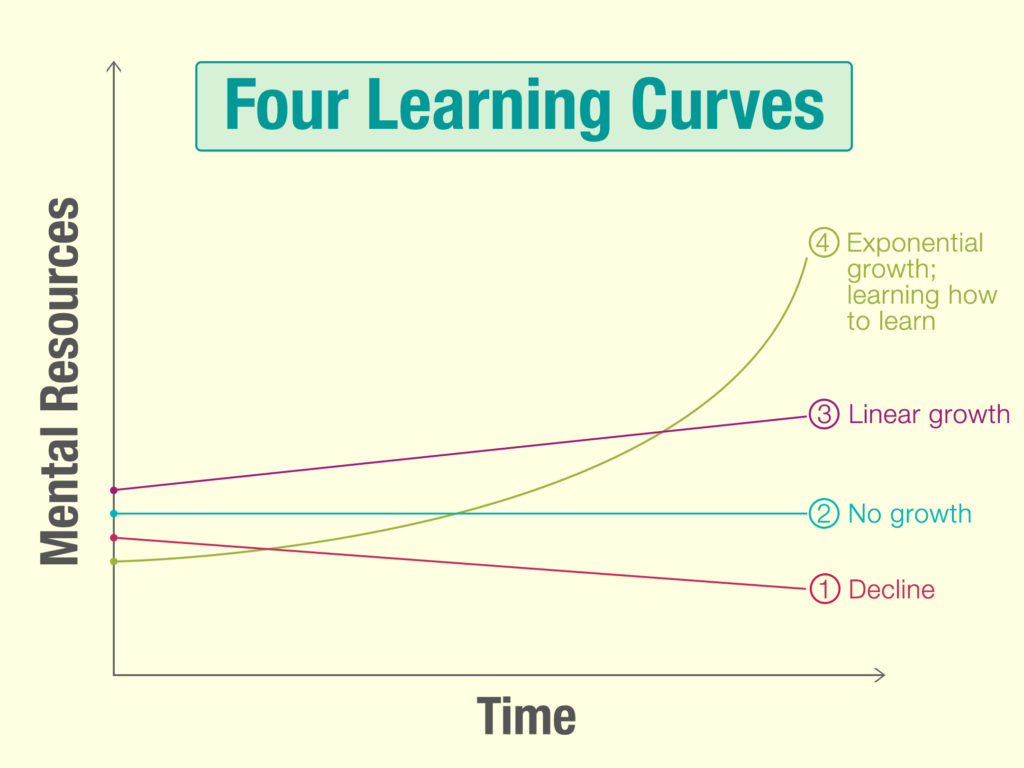

Learning is the strength of strengths, since it’s the one we use to grow the rest of them.

Knowing how to learn the things that are important to you could be the greatest strength of all.

14

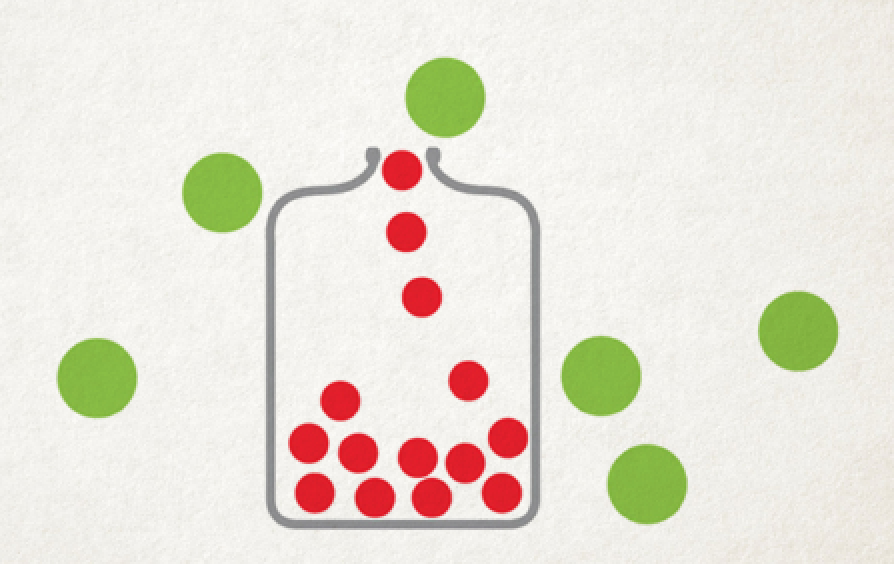

Velcro for Bad, Teflon for Good

15

15

The Negativity Bias

As the nervous system evolved, avoiding “sticks” was usually more consequential than getting “carrots.”

1. So we scan for bad news,

2. Over-focus on it,

3. Over-react to it,

4. Turn it quickly into (implicit) memory,

5. Sensitize the brain to the negative, and

6. Get into vicious cycles with others.

16

Taking in the Good

HEAL: Turning States into Traits

Activation

1. Have a beneficial experience

Installation

2. Enrich the experience

3. Absorb the experience

4. Link positive and negative material (Optional)

19

Have a Beneficial Experience

20

20

Enrich It

21

21

Absorb It

22

22

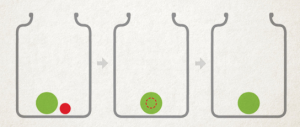

Link Positive & Negative Material

23

23

Have It, Enjoy It

24

24

Pick a partner and choose an A and a B (A’s go first). Then take turns, with one person speaking while the partner mainly listens, exploring this question:

What are some of the good facts in your life these days?

As the listener, keep finding a genuine gladness about the good facts in the life of your partner.

TIP: If you’re by yourself, reflect or journal.

25

It’s Good to Take in the Good

Develops psychological resources:

• General – resilience, positive mood, feeling loved, etc.

• Specific – matched to challenges, wounds, deficits

Has built-in, implicit benefits:

• Training attention and executive functions

• Treating oneself kindly, that one matters

May sensitize the brain to the positive

Fuels positive cycles with others

26

Keep a green bough

in your heart,

and a singing bird

will come.

-Lao Tzu

27

Growing Key Resources

Resilience is required for challenges to our needs.

Understanding the need that is challenged helps us identify, grow, and use the specific mental resource(s) that are best matched to it.

28

What – if it were more present in the mind of a person – would really help?

How could a person have and install more experiences of these mental resources?

29

Meeting Our Three Fundamental Needs

- Safety

Avoiding harms

- Satisfaction

Approaching rewards

- Connection

Attaching to others

30

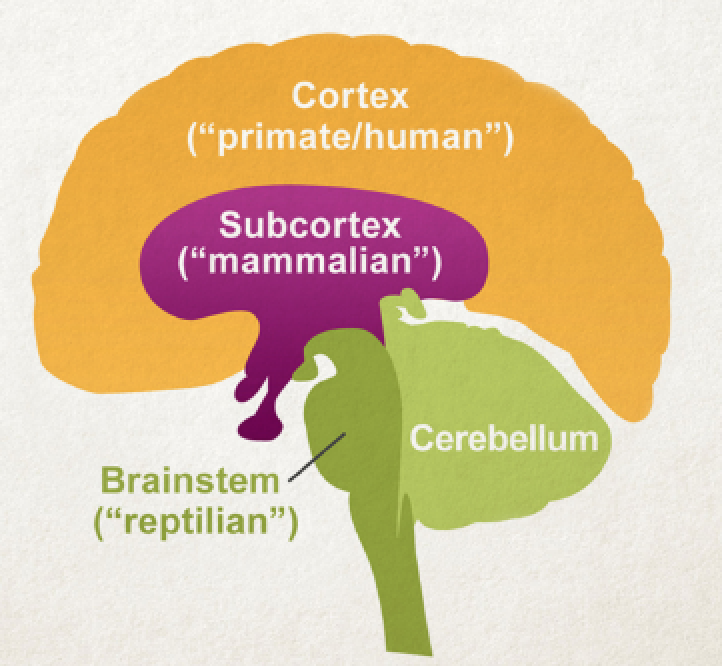

The Evolving Brain

31

31

Pet the Lizard

32

Feed the Mouse

33

Hug the Monkey

34

Coming Home

Peace

Contentment

Love

35

Matching Resources to Needs

Safety > Peace

See actual threats, See resources, Grit, Fortitude, Feel protected, Alright right now, Relaxation, Calm

Satisfaction > Contentment

Gladness, Feel successful, Healthy pleasures, Impulse control, Aspiration, Enthusiasm

Connection > Love

Empathy, Compassion, Kindness, Wide circle of “us”, Assertiveness, Self-worth, Confidence

36

Wider Implications

As we grow inner resources, we become more able to cope with stress, recover from trauma, and pursue our aims.

At the individual level, this is the foundation of resilient well-being.

37

At the level of groups and countries, people become less vulnerable to the classic manipulations of fear and anger, greed and possessiveness, and “us” against “them” conflicts.

Which has big implications for our world.

38

Think not lightly of good,

saying, “It will not come to me.”

Drop by drop is

the water pot filled.

Likewise, the wise one,

Gathering it little by little,

Fills oneself with good.

-Dhammapada 9.122

39

Supplemental Materials

Shaping the Course of a Life

Challenges

Vulnerabilities

Resources

40

Location of Resources

World

Body

Mind

41

Researchers have focused on identifying and using resources – such as workplace mindfulness – but what about developing them in the first place?

42

An Overview of Current Research

Much research on people that psychological practices lead to psychological benefits (with presumed neural correlates)

Much research on animals that various stimuli lead to changes in their brains (with presumed experiential correlates)

Some research on people that experiences change their brains

A little research on people about mental factors that increase social-emotional learning (SEL) (with presumed neural correlates)

One study on systematic training in mental factors of SEL

43

Key Mechanisms of Neuroplasticity

• (De)Sensitizing existing synapses

• Building new synapses between neurons

• Altered gene expression inside neurons

• Building and integrating new neurons

• Altered activity in a region

• Altered connectivity among regions

• Changes in neurochemical activity (e.g., dopamine)

• Changes in neurotrophic factors

• Modulation by stress hormones, cytokines

• Slow wave and REM sleep

• Information transfer from hippocampus to cortex

44

Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness.

Lazar, et al. 2005.

Neuroreport, 16, 1893-1897.

45

In the Garden of the Mind

1. Be with what is there

2. Decrease the negative

3. Increase the positive

Witness. Pull weeds. Plant flowers.

Let be. Let go. Let in.

Mindfulness is present in all three.

“Being with” is primary – but not enough.

We also need “wise effort.”

46

The Two Ways To Have a Beneficial Experience

- Notice one you are already having.

• In the foreground of awareness

• In the background - Create One.

48

Two Aspects of Installation

Enriching

Mind – big, rich, protected experience

Brain – intensifying and maintaining neural activity

Absorbing

Mind – intending and sensing that the experience is received into oneself, with related rewards

Brain – priming, sensitizing, and promoting more effective encoding and consolidation

49

Enriching an Experience

• Duration – 5+ seconds; protecting it; keeping it going

• Intensity – opening to it in the mind; helping it get big

• Multimodality – engaging multiple aspects of experience, especially perception and emotion

• Novelty – seeing what is fresh; “don’t know mind”

• Salience – seeing why this is personally relevant

50

Absorbing an Experience

• Intend to receive the experience into yourself.

• Sense the experience sinking into you.

– Imagery – Water into a sponge; golden dust sifting down; a jewel into the treasure chest of the heart

– Sensation – Warm soothing balm

– Give over to it; let it change you.

• Be aware of ways the experience is rewarding.

51

Four Ways to Use HEAL with Others

• Doing it implicitly

• Teaching it and leaving it up to people

• Doing it explicitly with people

• Asking people to do it on their own

52

HEAL in Classes and Trainings

• Take a few minutes to explain it and teach it.

• In the flow, encourage Enriching and Absorbing, using natural language.

• Encourage people to use HEAL on their own.

• Do HEAL on regular occasions (e.g., at end of a therapy session, at end of mindfulness practice)

53

Suggested Books

- See RickHanson.net for other good books.

- Austin, J. 2009. Selfless Insight. MIT Press.

- Begley. S. 2007. Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain. Ballantine.

- Carter, C. 2010. Raising Happiness. Ballantine.

- Hanson, R. (with R. Mendius). 2009. Buddha’s Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love, and Wisdom. New Harbinger.

- Johnson, S. 2005. Mind Wide Open. Scribner.

- Keltner, D. 2009. Born to Be Good. Norton.

- Kornfield, J. 2009. The Wise Heart. Bantam.

- LeDoux, J. 2003. Synaptic Self. Penguin.

- Linden, D. 2008. The Accidental Mind. Belknap.

- Sapolsky, R. 2004. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. Holt.

- Siegel, D. 2007. The Mindful Brain. Norton.

- Thompson, E. 2007. Mind in Life. Belknap.

Suggested References

- See www.RickHanson.net/key-papers/ for other suggested readings.

- Atmanspacher, H. & Graben, P. (2007). Contextual emergence of mental states from neurodynamics. Chaos & Complexity Letters, 2, 151-168.

- Bailey, C. H., Bartsch, D., & Kandel, E. R. (1996). Toward a molecular definition of long-term memory storage. PNAS, 93(24), 13445-13452.

- Baumeister, R., Bratlavsky, E., Finkenauer, C. & Vohs, K. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5, 323-370.

- Bryant, F. B., & Veroff, J. (2007). Savoring: A new model of positive experience. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Casasanto, D., & Dijkstra, K. (2010). Motor action and emotional memory. Cognition, 115, 179-185.

- Claxton, G. (2002). Education for the learning age: A sociocultural approach to learning to learn. Learning for life in the 21st century, 21-33.

- Clopath, C. (2012). Synaptic consolidation: an approach to long-term learning.Cognitive Neurodynamics, 6(3), 251–257.

- Craik F.I.M. 2007. Encoding: A cognitive perspective. In (Eds. Roediger HL I.I.I., Dudai Y. & Fitzpatrick S.M.), Science of Memory: Concepts (pp. 129-135). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Davidson, R.J. (2004). Well-being and affective style: neural substrates and biobehavioural correlates. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 359, 1395-1411.

- Dudai, Y. (2004). The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram?. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 55, 51-86.

- Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. Advances in experimental social psychology, 47(1), 53.

- Garland, E. L., Fredrickson, B., Kring, A. M., Johnson, D. P., Meyer, P. S., & Penn, D. L. (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical psychology review, 30(7), 849-864.

- Hamann, S. B., Ely, T. D., Grafton, S. T., & Kilts, C. D. (1999). Amygdala activity related to enhanced memory for pleasant and aversive stimuli. Nature neuroscience, 2(3), 289-293.

- Hanson, R. 2011. Hardwiring happiness: The new brain science of contentment, calm, and confidence. New York: Harmony.

- Hölzel, B. K., Ott, U., Gard, T., Hempel, H., Weygandt, M., Morgen, K., & Vaitl, D. (2008). Investigation of mindfulness meditation practitioners with voxel-based morphometry. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 3(1), 55-61.

- Hölzel, B. K., Carmody, J., Evans, K. C., Hoge, E. A., Dusek, J. A., Morgan, L., … & Lazar, S. W. (2009). Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, nsp034.

- Jamrozik, A., McQuire, M., Cardillo, E. R., & Chatterjee, A. (2016). Metaphor: Bridging embodiment to abstraction. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 1-10.

- Kensinger, E. A., & Corkin, S. (2004). Two routes to emotional memory: Distinct neural processes for valence and arousal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(9), 3310-3315.

- Koch, J. M., Hinze-Selch, D., Stingele, K., Huchzermeier, C., Goder, R., Seeck-Hirschner, M., et al. (2009). Changes in CREB phosphorylation and BDNF plasma levels during psychotherapy of depression. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(3), 187−192.

- Lazar, S., Kerr, C., Wasserman, R., Gray, J., Greve, D., Treadway, M., McGarvey, M., Quinn, B., Dusek, J., Benson, H., Rauch, S., Moore, C., & Fischl, B. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport, 16, 1893-1897.

- Lee, T.-H., Greening, S. G., & Mather, M. (2015). Encoding of goal-relevant stimuli is strengthened by emotional arousal in memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1173.

- Lutz, A., Brefczynski-Lewis, J., Johnstone, T., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: Effects of meditative expertise. PLoS One, 3(3), e1897.

- Madan, C. R. (2013). Toward a common theory for learning from reward, affect, and motivation: the SIMON framework. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 7.

- Madan, C. R., & Singhal, A. (2012). Motor imagery and higher-level cognition: four hurdles before research can sprint forward. Cognitive Processing, 13(3), 211-229.

- McEwen, B. S. (2016). In pursuit of resilience: stress, epigenetics, and brain plasticity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1373(1), 56-64.

- McGaugh, J.L. 2000. Memory: A century of consolidation. Science, 287, 248-251.

- Nadel, L., Hupbach, A., Gomez, R., & Newman-Smith, K. (2012). Memory formation, consolidation and transformation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(7), 1640-1645.

- Pais-Vieira, C., Wing, E. A., & Cabeza, R. (2016). The influence of self-awareness on emotional memory formation: An fMRI study. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 11(4), 580-592.

- Palombo, D. J., & Madan, C. R. (2015). Making Memories That Last. The Journal of Neuroscience, 35(30), 10643-10644.

- Paquette, V., Levesque, J., Mensour, B., Leroux, J. M., Beaudoin, G., Bourgouin, P. & Beauregard, M. 2003 Change the mind and you change the brain: effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on the neural correlates of spider phobia. NeuroImage 18, 401–409.

- Rozin, P. & Royzman, E.B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5, 296-320.

- Sneve, M. H., Grydeland, H., Nyberg, L., Bowles, B., Amlien, I. K., Langnes, E., … & Fjell, A. M. (2015). Mechanisms underlying encoding of short-lived versus durable episodic memories. The Journal of Neuroscience, 35(13), 5202-5212.

- Talmi, D. (2013). Enhanced Emotional Memory Cognitive and Neural Mechanisms. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(6), 430-436.

- Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. Harvard University Press.

- Wittmann, B. C., Schott, B. H., Guderian, S., Frey, J. U., Heinze, H. J., & Düzel, E. (2005). Reward-related FMRI activation of dopaminergic midbrain is associated with enhanced hippocampus-dependent long-term memory formation. Neuron, 45(3), 459-467.

- Yonelinas, A. P., & Ritchey, M. (2015). The slow forgetting of emotional episodic memories: an emotional binding account. Trends in cognitive sciences, 19(5), 259-267.