Neuroscience

Is it true that we only use a small amount of the brain's capacity? Why?

In a general sense, we actually need and use all of the brain’s capacity. The idea that we use just 10% or so is a myth. We would not have evolved an organ that uses 20-25% of the oxygen and glucose in our blood – even though it’s just 2-3% of our bodyweight – if we (and our ancestors) did not need every bit of it. That said, many people do not make the best possible use of their talents, skills, values, and opportunities. To me, that’s the much greater loss.

Can we do anything to increase the amount of the brain we use?

We can increase the brain’s functional capabilities by protecting it (e.g., avoiding or reducing injuries, toxins, drugs and alcohol, and stress) and by internalizing beneficial experiences – helping them get encoded into lasting changes in neural structure and function – in order to grow more inner strengths such as resilience, gratitude, self-compassion, kindness, insight into oneself and others, and overall well-being.

Unfortunately, this isn’t a process that will give us true “superpowers,” but doing so leads us to being happier ourselves and more helpful to others. To me, that’s a really wonderful superpower! There are also many examples of people who have really gotten the most out of their brain and body through intense training in music, sports, dance, or meditation, and developed some remarkable abilities because of it.

Can just reading the words which describe an experience bring activity to the corresponding part of the brain?

There is a lot of fMRI research in which the prompt to the subject in the scanner is reading a text.

Many of the texts used are emotion words or passages. So there are many examples of reading producing brain activity that is consistent with the experience the subject reports while reading the text. More specifically, if you mean reading about an experience per se, I don’t know of any specific studies about that, but there well may be. Bottom-line, if you read about an experience – say, a memoir of combat or rock-climbing or bar-hopping or commodities trading . . . or similar passages in fiction – and have a sense of that experience yourself while reading about it in someone else, then apart from the hypothetical influences of transcendental factors, by definition that mental experience must map one-to-one to underlying neural activity, and in the regions of the brain that represent that kind of experience (e.g., right hemisphere for imagery).

A parallel to reading would be imagining different experiences or behaviors. You might be interested in Sharon Begley’s book, Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain, in which she reports a study that piano players who simply imagined playing a certain piece of music for sustained periods grew cortex in motor regions of the brain that handled those particular finger movements. This article of mine might also be helpful: Mind Changing Brain Changing Mind.

Is the brain still evolving?

Biological evolution in humans takes thousands of years to show effects. On this time scale, the brain is indeed still evolving, but slowly. But cultural evolution can be very very fast (as anyone born in the 20th century has seen!). I am hopeful that our growing understanding of the three pounds of tofu-like tissue between our ears will lead to more evolved ways of treating each other.

After years of mindfulness meditation, my brain is being evaluated for a neurodegenerative disease. Why?

I am sorry to hear about the possibility of a neurodegenerative disease.

With respect, I’d offer that multiple things can be true side by side: mental activity changes the brain, mindfulness practice has many benefits including altering brain structure and function, and sometimes illness or dysfunction still comes our way. For me, acquiring an illness is nothing to be guilty about! Instead of the self-criticism implicit in guilt, self-compassion is called for, and gladness and self-respect for all the good practices you have been doing over the years.

Last, I am not aware of any research on this (though there might be some I don’t know about), but to me it is plausible that repeated mental training focused on what might be deteriorating (such as memory or motor control) could have benefits, at least in slowing the progression of illness or in strengthening compensatory factors or processes.

What can be done about ``neural reductionism`` when that seems to be our default mode of operation?

I’m not sure what is meant by “neural reductionism” here, but if it includes the popular notion of “reducing consciousness to brain processes”, then I think there are different levels of analysis and different categories of causes that need to be explored. I don’t think the behavior of mice and hawks in a meadow “reduces” to the chemical processes in their bodies, let alone the quantum processes, but there is certainly a relationship between one and the other.

Absent a resort to supernatural or transcendental factors, of course immaterial mental activity including consciousness – whether in humans, monkey, mice, or lizards . . . even spiders – must “reduce” to underlying material phenomena in the sense that the latter are necessary enabling and constructive conditions. But this does not mean that powerful ideas such as cultural helplessness or profound feelings such as love are “merely” electrochemical processes any more than the hunting behaviors of hawks are “merely” molecular processes. If you’re interested, check out some articles on Neurodharma in the Wise Brain Bulletin, which try to get at this; also my article The Mind, the Brain, and God.

Do you have any information on post-concussion syndrome (PCS) following a mild traumatic brain injury (TBI)?

While I’m not a specialist in this area, the one thing I have heard is the potential value of neurofeedback – especially from someone who has a lot of experience with it. Perhaps you could find a good person in your area. I presume you are working with medical professionals, too.

When using mindfulness as a recovery tool from an TBI, remember that persistence, gentleness, and curiosity are important factors. Persistence means a steadily increasing capacity for cognitive exertion. This will take effort and stamina but in the end it pays off. Maintain a gentleness towards yourself throughout the recovery process, with patience and perseverance, and keep curious about new possibilities or practices that will maintain your momentum towards recovery.

Meanwhile, to me common sense would include good brain health practices in general: try to disengage from stress as much as possible, look for opportunities for positive emotions, avoid toxins, and take high quality fish oil – and avoid any blows to the head.

Is an unconscous lip tick a brain/nervous system issue and is there anything I can do to correct it?

It sounds like you have a tic – and the medical fact is that almost everyone, me included, has these little motor habits. The most important thing is to try not to be anxious, stressed, or self-conscious about them. This secondary “collateral damage” cost of the tic is usually the worse thing about them, so try to relax, accept yourself, and keep things in perspective.

Additionally, if you want, you could talk with a therapist specifically about it. Perhaps it increases when you feel tense or there is some other trigger you could be mindful of. Then, as you notice the trigger, you could deliberately bring attention to that part of your body and interrupt the pattern of the tic, and perhaps also disengage from the trigger itself.

From a brain science perspective, tics are perfectly normal, simply a motor habit that gets accidentally acquired. The key to changing them is to disrupt them and acquire a different motor habit such as simply speaking in a normal way without the lip movements.

What suggestions do you have for recovering from a head concussion?

I am no specialist in head injury, but what I have seen myself or heard from people with more experience includes: Take a concussion really seriously.

Avoid any further blows to head, even seemingly minor ones.

Work with licensed, experienced professionals who really listen to you and take the concussion seriously. Explore neurofeedback.

Overall, treat your brain with kid gloves, such as minimize stress, prevent or reduce inflammation in general, eat brain health foods (e.g., refined fish oil or flax oil), avoid toxins (e.g., stand upwind when pumping gas), and encourage authentic emotionally positive experiences.

Is there a way to repair damage to the brain and hippocampus?

The hippocampus seems to be the key site in the human brain for neurogenesis (new baby neurons), though a recent study has raised questions about this finding. If neurogenesis in the hippocampus is indeed the case, exercise/activity stimulates neurogenesis, and complexity and stimulation help keep those new neurons alive and promote them getting wired into neural nets.

Existing neurons in the hippocampus can make new connections with each other, and with other parts of the brain. Other parts of the brain can help out to compensate for, say, a less-than-optimal hippocampus. For example, if a person knows that stress and trauma have made them prickly, presumably related in part to wear and tear on their hippocampi (two of them in the brain), then that person could draw on an intact prefrontal cortex to slow down and buy time and be less reactive.

Meanwhile, do mindfulness to disengage from negative reactions, and focus on taking in the good to replace them with resilient well-being.

Can neurofeedback help a hyperactive, far too easily agitated amygdala?

Neurofeedback can indeed sometimes be helpful. The key is to find an experienced practitioner and then give it one or a few sessions to see if it makes a difference.

You might like Heartmath’s Inner Balance program, biofeedback-oriented to train a calm and resilient heart-lungs system.

I'm interested in knowing more about neuroplasticity and the way our brains would rewire after stopping alcohol consumption.

I am not a specialist on substance abuse and dependence. The thoughts expressed here are informal and tentative, and I encourage you to explore these topics with true experts.

A lot depends of the total history of alcohol consumption, and personal factors such as age, weight, and gender. The long-term effects of mild consumption (in terms of weight, gender, etc.) on the brain may be fairly limited and relatively quickly reset after sobriety. Then the effects of no longer drinking would be felt more through psychosocial pathways (e.g., experiencing a loss of “fun” or stress relief) than through physiological pathways – though this is a very informal tentative uneducated view. Long-term moderate to severe drinking (defined relative to the particular individual) could affect neurochemistry in a variety of ways, as discussed in these articles: Alcohol and Neurotransmitter Interactions (1997), How Drugs Affect Neurotransmitters.

I doubt there is any particularly clear information about how long it takes to return key neurotransmitter systems back to their original healthy activity. It’s hard to assess neurotransmitter activity in humans . . . and how informative are invasive studies of rats?

The practical takeaways from the neural implications of alcohol consumption would be in sobriety to:

- Find other ways to relax and lower stress (compensating for the desensitization of GABA receptors).

- Find forms of enjoyment and “stimulation” that are both rewarding and relatively mellow (compensating for the hypersensitization of glutamate receptors and the disruption of dopamine activity).

- Through exercise and engaging complex mental activities, encourage neurogenesis in the hippocampus (compensating for the ways that high alcohol consumption damages and kills neurons).

- Through social support and other means, find ways to stay sober . . . one day at a time (compensating for the ways that alcohol consumption, especially intermittent high consumption, can alter the nucleus accumbens and other reward-seeking systems in the subcortex to crave alcohol even months or years into sobriety)

Of course, there are other useful actions in sobriety besides the neurally-informed ones noted above.

Can you explain the difference between the mind and the brain?

I use the word “mind” the way it is essentially used, most of the time, in neuroscience, to refer to the entirety of the information represented within the nervous system. We are surrounded by examples of different materials representing immaterial information: the physical hard drive of your computer stores and operates upon the non-physical information in your documents, music, and pictures; physical sound waves carry the intangible meanings of the words we use; and so on. In the same way, the brain represents, stores, communicates, and transforms the information that comprises the mind. Most of this information is forever outside awareness.

In effect, the mind is what the nervous system does, headquartered in the brain.

There may be a transcendental X factor – call it God, Spirit, or by no name at all – at work in awareness, in the mind in general, or in the universe altogether. Personally, I experience and believe that this is the case. But even without this possibility, the dots that connect mental activity and neural activity are getting clearer and clearer – giving us many opportunities to develop and use increasingly precise and powerful ways of using targeted mental activity to stimulate and therefore strengthen the neural substrates of wholesome states of mind.

Is it more accurate to say that the brain is both the hardware and software (i.e. operating system) and the mind comprises the data elements?

For me, the mind/brain (nervous system) distinction is at bottom the distinction between immaterial information and a material substrate that represents it. I think information is real and natural while being immaterial – but information requires a material substrate. And in the nervous system, unlike a chalkboard, information in turn shapes neural structure; the mind changes the brain.

In ways that remain mysterious, somehow the realm of immaterial information becomes experienced phenomenology – for octopi and cats as well as people.

And there could be transcendental X factors at work as well.

What exactly do you mean by “proximally sufficient condition?”

I was trying to say that the brain is “close” (i.e. proximal) to the mind . . . while also nodding in the direction of the fact that a brain is sufficient for a basic kind of mind – such as the experiences and information processing of, say, a monkey or a lizard – but for a truly human mind one also needs other enabling and facilitative conditions, such as exposure to language and other aspects of human culture.

I’ve found the work of Evan Thompson, specifically his book Mind in Life, to be deeply useful both intellectually and personally on this issue.

Where does the “fight or flight” response come from? Does it have to do with the primitive/reptile brain or the emotional brain?

These distinctions about the brain – fight or flight response, primitive/reptile brain, emotional brain – are used a lot these days, but they’re inherently fuzzy. The amygdala does initiate the fight or flight response through inputs into the hypothalamus (triggering the hormonal part of that response) and to brainstem control centers of the sympathetic nervous system (triggering the neural parts of that response). Some aspects of this response are emotional but some are not; and, complicating the distinctions further (among the fight or flight response, primitive/reptile brain, and emotional brain), some emotional shadings the amygdala is involved in don’t activate the fight or flight response. For example, the amygdala is involved in positive emotion processing. Some parts of our emotional life don’t involve the amygdala at all. See the complexities, here, in terms of the categories?

Plus, reptiles have a functioning basal ganglia, which is part of the subcortex on top of the brainstem and very involved in motivation, and to some extent, emotion. In the brainstem, there are nodes that can produce rage and fear, as well as nodes with oxytocin receptors (social system). The brainstem participates in emotion, and the so-called reptile brain is more than the brainstem: so, more complications. Also, the cortex is very involved in emotion, it’s not just the subcortex and brainstem: complications cubed!

“Amygdala hijack” just means that the thalamus inputs into the amygdala with sensory information (like positive “carrots” and negative “sticks”) arrives before those inputs get to the prefrontal cortex. So the amygdala gets a second or two head-start over the cooler reasoning processes coming down from the prefrontal cortex. Also, more generally, the brain as a whole participates in “emotional hijack” that goes beyond the amygdala alone. The amygdala part of the emotional hijack is often overstated: it’s just a small head start. Still, in cases of prior sensitization of the brain due to trauma, that head start could make a big difference.

Overall, I think there is a natural and fine flow in the culture in which there is an initial enthusiasm for a subject and overstatement and blurring of distinctions, and then a second wave comes through to clarify things. That’s what’s happening with these fields now.

Where do my negative or defensive reactions come from?

There is a common but mistaken idea these days: there is no particular neural “center” or “region” of emotional reactivity, including the brainstem.

And reactivity is not restricted to the safety needs that are also managed by the whole brain, though the primal roots of safety management (including literally keeping the heart beating) are grounded in the brainstem. You’ll see this conflation of emotional reactivity with the “reptilian brain” slash safety issues a lot in the culture and it’s just wrong . . . and weirdly prejudicial toward our little inner lizards! TONS of reactivity involve satisfaction/reward-seeking systems in the subcortex and connecting/attaching systems in the neocortex.

There’s also in the culture a simplistic conflation of neocortex/cognition/cool/thinking slow/reasonable/good, along with a related conflation of subcortex/emotion/hot/thinking fast/reactive/bad. Yes the neocortex enables conceptualizing and complex formal reasoning . . . . but it is full of crazy ideas and perspectives that makes us suffer and harm. Yes the subcortex enables the experience and effects of emotion . . . . but it also is the primary source of a background feeling of basic bodily well-being in the wallpaper of the mind.

In addition to the value of accuracy in its own right, another reason I try to flag these matters is because the frequent framing of the more ancient, nonverbal, and emotional aspects of the brain that we see in the culture sends us down a slippery slope toward the old views that emotion (and, um, women) is primitive and problematic while reason (and, um, men) is modern and civilized.

Can you explain what you mean by “The brain is like Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positives ones?``

As the brain evolved, it was critically important to learn from negative experiences – if one survived them! “Once burned, twice shy.” So the brain has specialized circuits that register negative experiences immediately in emotional memory. On the other hand, positive experiences – unless they are very novel or intense – have standard issue memory systems, and these require that something be held in awareness for many seconds in a row to transfer from short-term memory buffers to long-term storage. Since we rarely do this, most positive experiences flow through the brain like water through a sieve, while negative ones are caught every time. Thus my metaphor of Velcro and Teflon – an example of what scientists call the “negativity bias” of the brain.

The effects include: a growing sensitivity to stress, upset, and other negative experiences; a tendency toward pessimism, regret, and resentment; and a long shadows cast by old pain.

How do I mesh the two tendencies of the brain: to be alert and tense, and its default setting of calm and contentment?

Basically, I think the evidence is that both are true: there is an ongoing trickle of background anxiety to keep us vigilant, and there is also a strong inclination to default to the “responsive mode” of being peaceful, happy, and loving when we are not disturbed. Putting these two apparent facts together, I think the trickle of anxiety prompts us to scan for threat, but if we find that all is well for now, then we default to the responsive mode, and then this cycle repeats itself a moment later. For me the pragmatic point is to discern real threats and address them, while also recognizing the strong bias from evolution to look for threats behind every bush and thus appreciating the importance of exerting compensatory influences in a variety of ways, from inner practices such as I focus on to social support and (hopefully) decent health insurance.

Do you know whether brains of people raised in non-western, cultures like Bhutan or Tibet have the Velcro/Teflon wiring?

Great question!

I don’t think there are any scientific studies on this particular topic – though there is a lot of general research on the universal nature of the fundamental properties of the human brain, that cross cultures. Interestingly, there is much less genetic variation among the members of the human species than among the other primates; apparently, there were several “choke points” in our evolution when less than 100,000 thousand (and at one point around only 15,000 “Java Men” lived: in effect, they were an endangered species at that time). So we all have pretty similar brains, which all do have an evolved tendency toward threat scanning/reaction/memory storage. Then psychological factors shape the expression of those tendencies, including the loving and positive culture of Bhutan and Tibet. In a nutshell, two things are both true: we have strong tendencies toward negativity and craving, but we also have strong capacities to develop peacefulness, happiness, and love – and I believe these are in fact much stronger! But we must use them, as so clearly the Dalai Lama and others have done.

Why do people 'beat themselves up'? What process is behind that?

I think people beat themselves up – which is different from healthy guidance of oneself (which includes appropriate winces of remorse or shame) – for two reasons: too much inner attacking, and too little inner nurturance. These two forces in the mind are out of balance. Why? Multiple reasons, including individual differences in temperament (some people are more prone to anxiety or grumpiness). But for most people the primary sources are what they have internalized (especially as a child) from their family, peers, and culture. Then, once harsh self-criticism has been internalized along with insufficient internalization of self-nurturance, beating oneself up can take on a life of its own, both as simply a habit and as a way (that goes much too far, at considerable cost) to avoid the possibility of making mistakes or looking bad in front of others.

Whole networks of neurons and related and complex physical processes (e.g., neurotransmitter activity, epigenetic processes) are the basis for acquiring fears, including because a person has been on the receiving end of much anger from others. In other words, learning occurs: emotional, social, somatic, motivational, attitudinal learning: enduring changes in neural structure or function due to a person’s experiences. Check out Joseph LeDoux and the learning of anxiety and fear.

The amygdala also flags experiences as personally relevant, with a bias in most people’s brains toward flagging what is negatively relevant. Then the hippocampus gets involved, tagging that relevant experience for storage. (I’m simplifying a complex process, that also involves other circuitry in the brain.) The amygdala and hippocampus have receptors for various neurochemicals, including oxytocin, and over time these subcortical parts of the brain (two of each, on either side of the brain) can be modified by our experiences; in effect, they “learn,” too.

What changes in our brains when we decide to repeatedly focus on the way we think about and react to situations in our lives?

In practical terms, learning – brain change – is a two-stage process in which an activated experience must be installed through some kind of lasting change in neural structure or function. We become happier through having repeated experiences of happiness and related factors that get encoded – installed – into the brain.

Without installation, there is no learning, no change: in effect, the experience is wasted on the brain. This is the dirty little secret in most psychotherapy, human resources training, coaching, addiction recovery, and character education: most hard-won beneficial states of mind are momentarily positive but have no lasting value. That’s why many efforts to develop deep inner strengths in people are largely if not completely ineffective: they are indeed being fostered – but without deliberate mindful attention to sustaining them, feeling them in the body, and intentionally absorbing them into oneself, they just don’t get encoded much into the brain. The person may have a memory of a harrowing sailing trip or an intense week with Outward Bound, but is still basically just as vulnerable to stress, loss, or setbacks as ever because they didn’t “take in” those experiences.

Here is the key takeaway: it is commonplace to activate experiences of love, support, determination, endurance, and tenacity. What is rarer and more important is to bring skillful attention to installing these experiences in the brain so that they have enduring benefit for the person. The good news is that this skillful attention can be readily developed, as we found in the research on my training in positive neuroplasticity, and as explored in Hardwiring Happiness. But we have to do the work 5, 10, 20 (usually enjoyable) seconds at a time. Then we know in our hearts that we have earned the results – which makes the strength that we develop even sweeter.

Your work is based on the idea that meditation and mindfulness can change the brain. Can you expand on this?

Actually, I’d put this a little more broadly: my work – and that of many other scholars and clinicians – is grounded in the general fact of “experience-dependent neuroplasticity,” which is the capacity of mental activity to change neural structure.

For example, researchers studied cab drivers who must memorize London’s spaghetti snarl of streets, and at the end of their training their hippocampus – a part of the brain that makes visual-spatial memories – had become thicker: much like exercise, they worked a particular “muscle” in their brain, which built new connections among its neurons. Similarly, another study found that long-term mindfulness meditators had thicker cortex in parts of the brain that control attention and are able to tune into one’s body.

In the saying from the work of the Canadian psychologist, Donald Hebb: “neurons that fire together, wire together.” Fleeting thoughts and feelings leave lasting traces in neural structure. Whatever we stimulate in the brain tends to grow stronger over time.

A traditional saying is that the mind takes the shape it rests upon. The modern update would be that the brain takes its shape from whatever the mind rests upon – for better or worse. The brain is continually changing its structure. The only questions are: Who is doing the changing: oneself or other forces? And are these changes for the better?

In this larger context, my focus is on how to apply these new scientific findings: how to use the mind to change the brain to change the mind for the better – for psychological healing, personal growth, and (if it’s of interest) deepening spiritual practice. I’m especially interested in: How the brain has been shaped by evolution, giving us problematic tendencies toward greed, hatred, heartache, and delusion (using traditional terms) as well as wonderful capacities for happiness, peace, love, and wisdom. For example, we have a brain that makes us very vulnerable to feeling anxious, helpless, possessive, fixated on short-term rewards, angry, and aggressive. These qualities helped our ancestors survive and pass on their genes, but today they lead to much unnecessary suffering and conflict on both personal and global scales.

“Neurologizing”, the deep Buddhist analysis of the mind: what is going on inside the brain when a person is caught in the craving that leads to suffering? Alternately, what is happening in the brain when a person is experiencing equanimity, lovingkindness, meditative absorption, or liberating insight? Using neurologically-informed methods to help overcome our ancient inclinations to fear, dehumanize, exploit, and attack “them” so that 7 billion of us can live in peace with each other on our fragile planet.

In sum, this brain stuff can sound exotic or esoteric, but in essence the approach is simple: find the neural processes that underlie negative mental factors, and reduce them; meanwhile, find the neural processes that underlie positive mental factors, and increase them. Less bad and more good – based on neuroscience and Western psychology, and informed by contemplative wisdom.

Of course, much is not yet known about the brain, so this approach is necessarily an exploration. But if we remain modest about what we don’t know, there are still many plausible connections between the mind and the brain, and many opportunities for skillful intervention for ourselves, for our children and others we care for, and for humankind as a whole.

Why is neuroplasticity important, and how do you use it in your work?

My focus is on how to apply the new scientific findings around neuroplasticity: how to use the mind to change the brain to change the mind for the better – for psychological healing, personal growth, and (if it’s of interest) deepening spiritual practice. I’m especially interested in:

- How the brain has been shaped by evolution, giving us problematic tendencies toward greed, hatred, heartache, and delusion (using traditional terms) as well as wonderful capacities for happiness, peace, love, and wisdom. For example, we have a brain that makes us very vulnerable to feeling anxious, helpless, possessive, fixated on short-term rewards, angry, and aggressive. These qualities helped our ancestors survive and pass on their genes, but today they lead to much unnecessary suffering and conflict on both personal and global scales.

- “Neurologizing”, the deep Buddhist analysis of the mind: what is going on inside the brain when a person is caught in the craving that leads to suffering? Alternately, what is happening in the brain when a person is experiencing equanimity, lovingkindness, meditative absorption, or liberating insight?

- Using neurologically-informed methods to help overcome our ancient inclinations to fear, dehumanize, exploit, and attack “them” so that 7 billion of us can live in peace with each other on our fragile planet. Brain stuff can sound exotic or esoteric, but in essence the approach is simple: find the neural processes that underlie negative mental factors, and reduce them; meanwhile, find the neural processes that underlie positive mental factors, and increase them. Less bad and more good – based on neuroscience and Western psychology, and informed by contemplative wisdom.

Of course, much is not yet known about the brain, so this approach is necessarily an exploration. But if we remain modest about what we don’t know, there are still many plausible connections between the mind and the brain, and many opportunities for skillful intervention for ourselves, for our children and others we care for, and for humankind as a whole.

Can anyone develop a “buddha brain” — even people struggling with mental illness or depression?

Definitely!

First, a “buddha brain” is simply one that knows how to be truly happy in the face of life’s inescapable ups and downs. (I don’t capitalize the word “buddha” here to focus on the original nature of the word – which is “to know, to see clearly” – to distinguish my general meaning from the specific historical individual known as The Buddha.) The possibility of this kind of brain is inherent in the human brain that we all share; any human brain can become a buddha brain. Therefore, a buddha brain is for everyone, whatever their religious orientation (including none at all).

Second, we all must begin the path wherever we are – whether that’s everyday stress and frustration, mental illness, anxiety, sorrow and loss, or depression. In any moment when we step back from our experience and hold it in mindful awareness, or when we begin to let go of negative feelings and factors, or when we gradually turn toward and cultivate positive feelings and factors we are taking a step toward developing a buddha brain. Each small step matters. It was usually lots of small steps that took a person to a bad place, and it will be lots of small steps that take him or her to a better one.

Third, mental anguish or dysfunction can help us grow. They teach us a lot about how the mind works, they can deepen compassion for the troubles and sorrows of others, and, frankly, they can be very motivating. Personally, the times in my life when I have been most intent on taking my own steps toward a buddha brain have been either when I was really feeling blue – and needed to figure out how to get out of the hole I was in – or when I was feeling really good, and could still sense that there had to be more to life than this, and more profound possibilities for awakening.

How could you measure clinical interventions that encourage new cell growth and happiness?

This question gets at the remarkable fact under our noses all day long: our ineffable thoughts and feelings are making concrete, physical, lasting changes in the structure and function of our brains. Neurons that fire together, wire together. This is learning, including the emotional, motivational, attitudinal and skills learning that is our focus in therapy. In other words, the making of memory – especially implicit memory, the storehouse of emotional residues of lived experience, knowing “how to,” expectations, assumptions, models of relationship, etc. distinct from explicit memory, the much smaller storehouse of specific recollections and knowing “about” – the gradual change of the structure and function of the brain.

In this context, any kind of mental change is evidence of neural change. Since neuroscience is a baby science, our current, noninvasive, imaging technologies have limited capacities to measure neural change in human beings – especially given how physically fine, fast, and complex these changes are. You could put five of the cell bodies of a typical neuron side by side in the width of just one of your hairs, and five thousand of the synapses, the connections, between neurons in the width of just one hair.

Nonetheless, even though the ethics of animal research trouble and even alarm many, including me, it is the case that more invasive research on animal learning – including emotional, motivational learning, that has some parallels to therapy – has established many fine-grained details of the ways in which experiences of stress, frustration, and trauma, as well as experiences of caring, success, and safety change the nervous system.

So we presume that neural change must be occurring if there is mental change. In this light, there are now many studies with human beings that show structural and functional changes after interventions such as training in mindfulness, compassion, body awareness, and psychotherapy. The cortex – the outer shell or “skin” of the brain – gets measurably thicker due to new synapses and greater infusion by capillaries for blood flow; key regions are more readily activated; there is also greater connectivity between regions, so they are more integrated and work better together; there are even changes in the expression of genes – tiny strips of atoms in the twisted up molecules of DNA in the nuclei of neurons.

And as your mind changes your brain for the better, these changes in your brain feed back to change your mind for the better as well. As these positive structural and functional changes in the brain occur, people become more capable and happy. For instance, training in mindfulness increases activation in the left prefrontal cortex, which supports a more positive mood.

As to new cell growth, I assume this is a reference to neurogenesis, the birth of new baby neurons, primarily in the hippocampus. We can encourage the birth of these neurons through exercise, and encourage their survival and wiring into memory networks through engaging in complexity and stimulation. Here’s the takeaway: we can be confident in our own lives, and in our work with clients, that our efforts are bearing fruit in actual, physical changes in the nervous system. And since motivation is one of the primary factors shaping outcome in psychotherapy – and in life as a whole – this is heartening, wonderful news.

In your understanding, what are the limits of brain plasticity?

As you imply, most neuroplasticity is subtle and local, and does not change the overall architecture of the brain. I also think it is possible that there are individual variations in organic capacity for changing the brain, though I haven’t seen any studies on that (though they may exist).

I think a good starting point is to consider the vast diversity of human cultures, and the many individual examples of vast psychological changes – for better or worse – over the course of one person’s life. These illustrations of great mental plasticity are evidence for great neural plasticity in high impact ways, even if the vast majority of the synapses and circuits of the brain are unchanged.

The takeaway for me from this line of thinking is to appreciate the importance of hard work, of making little efforts each day that add up over time, to change your brain and thus your life for the better. And there’s a takeaway in terms of never betting against human potential and the human heart. Most of us have no idea how much we could grow psychologically or spiritually if we really gave ourselves to it, and put at least as much effort into it as we put into our occupation – or even our golf game!

How is the brain changed specifically by doing the practices you suggest?

As a broad principle, the brain regions or processes that are activated by an experience are the ones whose structure or function is most likely to be changed by the activation.

Neuroscience is a baby science, with much that’s not known. There’s much that may be plausible that doesn’t yet have a specific study to back it up. This said, the conceptual, perspective aspects of the practice of reminding yourself mentally that everything is impermanent would tend to engage prefrontal areas that do conceptual processing, and with repetition and conviction, produce lasting changes there, i.e., learning, adopting, developing the habit of a new view.

Also, the physical and emotional relaxation that would come with accepting transience would likely involve decreased sympathetic nervous system activity, increased parasympathetic nervous system activity, decreased stress hormones, and increased reward- and pleasure-related neurotransmitter activity (e.g., dopamine, natural opioids). With repetition, duration, and intensity of the experience, there would tend to be gradual changes in the resting state and responsiveness of these neural processes.

Last, evidence of mental change is evidence of neural change. Otherwise we are left with supernatural explanations. So if a person feels different or acts differently, something must have changed at the level of the body, particularly the brain.

Does brainwave optimization work or is it a scam?

Regarding brainwave optimization, brainwaves just track what is happening, they are not causally beneficial themselves. This said, personal practices (e.g., taking in the good, meditation, relaxing while walking the dog) can optimize brainwaves. I think you are referring more specifically on neurofeedback and things like Holosync that are essentially biofeedback devices/programs aimed at the brain. Generally, I think they are great IF they work for a person. Sometimes they do and sometimes they don’t.

From a pragmatic standpoint, bottom-line, does something help or hurt, including compared to alternatives. And of course, once a practice of any kind, including with brainwave devices, has induced a beneficial state (thought, feeling, etc.), be sure to internalize it so it has lasting value, woven into your nervous system.

What can be done to elicit the desired response and inhibit the undesired one, for those experiencing high levels of self-criticism?

- The direct way to grow a psychological resource is to experience (“activate”) it in order to “install” it. But sometimes that is challenging or upsetting. So we grow factors of this resource through experiences of these factors that are more accessible. Let’s say the direct experience of self-compassion is hard for the reasons you very insightfully identify. But the experience of a factor of self-compassion – such as the concept that justice applies to oneself as well as to others, or the capacity to calm the body when upset – might be within reach.

- In order to tolerate resource experience Z, we may need to grow resource Y . . . but perhaps experiencing Y is also reactivating and challenging. So then we grow resource X that enables us to experience and grow Y so that . . . we are now able to experience Z and thereby grow it. For example, training in mindfulness (X) could promote the capacity to experience body sensations in general without being flooded (resource Y), and developing this Y could enable a person to experience self-compassion (Z) more directly.

The distinction between 1 and 2 blurs in practice. The main difference is that 2 is more deliberately and planfully sequential, and is a road map for therapists and also for people in general.

What are the neurophysiological correlates of the distracting (and potentially helpful) states of mind?

Your question is deep and important – and the subject of considerable research. Check out what’s being done on the default network and mind wandering. Also see Farb’s research on the brain’s medial and lateral networks; my own take-off on this work can be found in my slidesets on Being and Doing.

A person can be in the present moment while (presently) planning the future or reflecting on the past. And being lost in reverie is not necessarily involving judging or comparing or planning. I suspect that sustained present-moment awareness primarily involves a recursive loop between the anterior cingulate cortex (for executive control of attention) and the insula (for an ongoing “map” of the body and emotions).

What happens with mindful eating?

Mindful eating would naturally down-regulate stress activation plus increase experiences of fulfillment and satiation that would reduce craving and thus suffering – of course via the various neural substrates of these mental processes.

The primary identified neural correlate of mindfulness – defined as sustained attention to something, typically with a meta-cognitive element of awareness of awareness (i.e., the Pali term for mindfulness, sati, has its root meaning in “recollectedness”) – is activation of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and related PFC executive control circuits that manage the deliberate control of attention. The term mindfulness sometimes is reduced to choiceless awareness, which is a common but serious error; choiceless awareness is simply a stance toward the stream of consciousness, and one can be mindful of both that stream and the stance much as one could be mindful of one’s golf swing, the flicker of expressions on the face of one’s partner, or what happens in the mind when one eats slowly and with focused attention. When mindful attention is applied to eating, it’s very plausible that the insula would be activated, which handles interoception.

Mindful eating would plausibly affect the body by:

- Down-regulating sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation, along with their related stress hormones; get benefits of less allostatic load

- Up-regulate parasympathetic activation; benefits of relaxation

- Strengthen ACC and related PFC circuits; benefits of improved attentional control and executive functions

- Strengthen insula; benefits of improved self-awareness and empathy for emotions of others (insula does both)

- Increase signaling to hypothalamus of visceral rewards received; benefits of reducing wanting and craving

How can you erase negative associations in neural structure rather than overwriting them?

When something bad happens the brain sometimes starts to associate neutral stimulus with negative stimulus. There’s been a lot of study on this with animals. A few human examples might be being in an elevator after having a panic attack in one, or working with an authority figure when you’ve had issues with authority in the past, or being outside in the dark after being assaulted out in the dark, or speaking from the heart when that was shamed when you were young. The situations are not inherently bad, but over time we build up negative associations with them because we’ve been hurt in the past. It’s the classic idiom – once burnt, twice shy.

In studies on rats, and also in new studies with humans, the key is (A) the activation of the learned link between the neutral and the negative stimulus, and (B) the repeated activation of the neutral stimulus with no negative associations during the window of re-consolidation.

In practical terms, this would be a matter of surfacing a person’s association between a neutral and negative stimulus, and helping them understand conceptually (at least) that the neutral stimulus is actually inherently neutral. Then, after this process, repeatedly reactivate the neutral stimulus with no negative associations for the next hour or so.

Minimally, you could reactivate the neutral stimulus with neutral associations. And for maximum effect, I think it could be useful to associate the neutral stimulus with authentic positive associations, which you can think of as “antidote experiences.”

If you focus on the positive for long enough, does it actually make your brain more receptive to doing that?

Research shows that repeated practice of any positive behavior (e.g., gratitude) will increasingly incline the mind in that direction. Presumably, since all mental activity and changes entail neural activity and changes in brain structure, this changing inclination of mind must involve enduring changes in neural networks and activations.

More specifically, there is much research showing that negative experiences gradually sensitize neural networks, including for memory, in a negative direction. I don’t know of any specific studies describing an opposite effect, though there are studies showing that positive experiences and thoughts can gradually desensitize negative sensitization. This said, it’s plausible to me that a person could gradually sensitize the brain to “the good” since sensitization is such a general dynamic/mechanism in the brain – thus making the brain like Velcro for the positive. This has certainly been my own experience; I feel like I am much faster than I used to be at registering a positive experience so it “sticks to my ribs.”

Do we have to savor an experience for 10-20-30 seconds to allow it to install in the brain’s circuitry as a resource?

Extending the duration of a beneficial experience will indeed tend to increase its consolidation/installation in memory – especially implicit memory for sensations, emotions, attitudes, intentions, etc.

This would apply to all experiences in general that we hope will lead to lasting changes in neural structure or function – learning, in the broadest sense – including those experiences that we wouldn’t tend to think of “savoring,” such as an insight into oneself or others, healthy remorse, the sense of how to be more skillful in a relationship, or clarity of resolution about how to act differently in the future.

There is a little bit of research on how the duration of an experience affects its lasting impact on a person (i.e., learning), but on the whole it is remarkable how little research there is on what a person can do inside her own mind – such as extending their duration – to increase the durable gain from the experiences she is having. I’ve had to pull together research from many corners, including on non-human animals, to identify “learning factors” that could plausibly be used by individuals to steepen their growth curves, healing curves, from the experiences they are having.

So I try to be modest about what I suggest, and emphasize how it is plausible, it can’t hurt, and we need more research. Bottom-line, I suspect that there is a minimum duration of at least a few seconds for the emotional/somatic/social/etc. residues of a “typical” beneficial experience to have a chance to begin their slow process of consolidation as lasting physical changes in the brain. (“Million-dollar moments” might take a little less time to start being consolidated.) Once that threshold is met, then I think it is plausible and certainly not contradicted by research that there is a kind of “dosing effect” in which extending the duration of the experience by 5-10-20 seconds or longer tends to increase its consolidation.

Are brain supplements backed by scientific evidence of their effectiveness?

I appreciate your comment, and share your stickler-ness! As to supplements, there is considerable published evidence for the efficacy of nutrients such as essential fatty acids or B-vitamins as supports for mood if there is a deficiency. There is also considerable research support for supplementing 5-hydroxytryptophan for mild to moderate depression.

As context, you may know of the recent high profile finding in Great Britain that there was no research evidence at all for about half of all medical practices. This does not mean that the practices are bad; as you know, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. But it does suggest that there is double standard in insisting on research evidence for nutrients the body has evolved to metabolize but not insist on research evidence for off-label uses of medications that are artificial molecules the body did not evolve to metabolize.

Also as context, in America medical error is the third leading cause of death, about 200,000 fatalities a year here, the great majority due to problems with medications. By comparison, the risks of things like essential fatty acids or B-vitamins are vastly smaller.

Personally, I have known people who are dogmatically holistic as well as people who are dogmatically anti-holistic. In my own case I try to find the path between the two.

What do you mean by ``your intentions will be aligned with each other at all levels of the neuroaxis: that’s when they have the most power?”

Think of the brain as a house with three floors: brainstem, sub-cortical tissues (e.g., hypothalamus, amygdala, basal ganglia, hippocampus), and cortex. The “neuroaxis” is just a way of talking about this vertical arrangement. Loosely speaking, the brainstem is about arousal and passion, the subcortical regions are about emotion and motivation, and the cortex is about planning and decision-making. In essence, the sentence you zeroed in on (which is sort of vague, you’re right) means: “Have intentions that are fueled by passion, emotionally rewarding (supporting motivation), and well-considered with a plan to bring them to fruition.”

What methods can you recommend to help boost memory?

I suggest starting by making sure you are in super health and ruling out any physiological factors. I’m not a physician, but have heard that things like estrogen imbalances, yeast overgrowths, etc. can affect memory.

Doing mental activities that work the memory “muscles” could help. Like playing bridge and having to remember key cards, learning a new language, or taking a class that calls for considerable memorization.

And if you’re not doing meditation routinely, I suggest it, too. Among its benefits are strengthening executive oversight of mental processes, which aids memory plus provides more influence over one’s thinking.

How might the increase in autism and related challenges be connected to the evolution of the brain and modern day living?

If I understand you correctly, the biological evolution of the brain, like any bodily organ or system, occurs over hundreds and usually thousands or tens of thousands of generations. So there hasn’t been time for the brain to evolve physically – such as increasing underlying causes of autism – in the handful of generations since 1900.

The causes of autistic spectrum disorders (including Asperger’s and PDD) remain mysterious and controversial. It’s possible that there could indeed be a connection between modernity and autism, though whether this hypothetical connection occurs via the brain or via other organs or systems (e.g., the immune system) is an open question.

Do you think playing computer solitaire fulfills the goal of mindfulness and meditation?

Well, with all the respect in the world for your mother – and as someone who works with children and routinely says that a mother’s intuition is gold – I’ve got to come down on your side here.

Sure, the “circle” of mental activities – and thus the neural processes and gradually building of neural structure – of meditation overlaps the “circle” of these while playing solitaire on the computer (or playing other games in other ways), but there is a lot about each circle that is distinct from the other one. Game playing will strengthen intellectual and other cognitive capacities (e.g., visual processing, perceptual analysis) that meditation will not.

On the other hand, meditation will building other capacities, such as strengthening attention (because of the relatively non-stimulating nature of breath sensations or other common targets of contemplative attention), the capacity to disengage from mental processes to observe them peacefully rather than getting swept away in chasing mental carrots or dodging mental sticks, and insight into both personal psychological material (e.g., the hurt lingering underneath resentments) and the general nature of mental phenomena as transient and usually not worth getting one’s knickers in a twist about. Plus meditation confers many other benefits, including stress reduction, managing anxiety, and reducing the distress and sometimes symptom intensity of many medical conditions.

While intellectually stimulating activities such as game playing have been shown to help protect against cognitive decline with aging, preliminary studies have also shown that religious and spiritual activities (which include prayer and meditation – though a person can meditate outside a religious frame and still get most if not all of its mental and thus neural benefits) also offer protections against cognitive decline, here too through overlapping “circles” of factors.

Bottom-line: I say do both! Have fun with solitaire, and find some contemplative practice that suits you. If you like, commit to meditating at least one minute a day, even if it’s the last minute before you fall asleep. And like many things, there is a dosing effect: the more meditation you do, the better for your brain.

Does meditation utilize the social circuitry of the brain?

While there are parts of the brain that enable important social functions (e.g., the insula is involved in empathy for the emotions of others), those parts also do many other important things (e.g., insula handles interoception). Saying meditation utilizes the social circuitry of the brain is like saying that meditation utilizes the executive circuitry of the brain, or the sensorimotor circuitry of the brain, or the gestalt processing functions of the brain – which it does. The brain uses hundreds of little capacities, little modules, arrayed in an architecture of complexity and evolutionary recency to perform just about any complex function, from riding a bike or talking with a friend to playing chess or meditating. It’s the function that is the organizing principle, not the underlying neural substrates.

What can be done in order to support a shrunken hippocampus?

In terms of how chronic stress and thus cortisol can damage the hippocampus, there are five kinds of good news:

- New baby neurons are born in this part of the brain, encouraged by exercise and stimulation.

- Existing synapses in the hippocampus can form new connections with each other.

- Other parts of the brain can compensate, like the prefrontal regions that we can draw on if we slow down our emotional reactions by a few seconds.

- We can grow other psychological resources, embedded in neural structure and function, such as positive emotions, mindfulness, and wholesome intentions.

- We can treat ourselves well, with compassion and encouragement and respect – thereby treating ourselves like we matter even if others didn’t (or don’t).

Is the experience of peace and happiness synonymous with activating the parasympathetic wing of the nervous system? If so, what are the three most successful techniques for activating the PNS?

It’s a great question, since there is sometimes a misunderstanding of the nervous system that equates parasympathetic activation with positive states of being and sympathetic activation with negative states.

Yes, activating the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) can foster the calming and easing that underlie many positive states of being. On the other hand, excessive PNS activation leads to the “freeze response” – in humans this is the equivalent of animals playing dead – which can feel like sleepiness, dissociation, inertness, numbing, tuning out, or shutting down, often accompanied by negative emotions such as dread or shame.

And yes, activating the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) can foster fight or flight states of being, often with associated negative emotions such as anger or fear. On the other hand, SNS activation combined with positive emotions such as eagerness, confidence, success, pleasure, affection, and gratification can foster wholesome actions such as cheering on your child in a race, making love, asserting yourself, dancing with your whole heart, or pursuing an ambition. Overall, a balance of PNS and SNS activation is best. In a culture that prizes SNS activation (and which often stimulates negative emotions such as drivenness or envy), it is particularly important to be strong and skillful in PNS activation. And throughout, keep planting and nourishing seeds of positive emotions, thoughts, somatic states, and desires.

In terms of what activates the PNS, anything that helps you relax will do this. If you want three “go-tos” that I like myself, here they are:

- Exhaling

- Touching your lips

- Hugging someone you care about

Do you have any articles that address short term memory and ability to read information?

I feel for those with memory issues. I assume/hope that if you do experience this, you have worked with licensed healthcare professionals about them. Here are some thoughts:

- I’m not offering medical advice here, and please discuss my comments with your doctor(s). You may have already pursued some if not all of them.

- I suggest you consult with a neurologist, including to rule out any issue with your brain itself.

- You could read up on what’s called the cytokine theory of depression, about how stress and inflammatory processes can affect the brain.

- If you are old enough for this to be relevant, talk with your gynecologist or a endocrinologist about how changes in estrogen and related reproductive hormones could be affecting your memory, and if so, what you might be able to do about that.

- Regular exercise might help.

- Be thoughtful about anything that might be inflammatory for you, including in your diet.

- You could try Lumosity type training. The reviews on it are mixed, but you might see for yourself what you get out of it, if anything.

- You could consult with a physician practicing “functional medicine” to get a fine-grained overall assessment and to explore possible factors in your body such as dysbiosis in your GI tract or less than optimal metabolism that might be affecting memory or other kinds of neural functioning.

Do you believe that depression can be healed without lifelong medication or do you see it as a chemical imbalance in the brain?

My view and the research evidence is not either/or (meds or no meds). If depressed mood is caused mainly or entirely by a physical health problem (distinct from “imbalance of brain chemistry,” such as an inflammatory condition, poor nutrition leading to significant deficiencies of B vitamins, etc.) or by a life condition (e.g., dreary work, poverty, abusive partner), then changing those causes alone could lift mood.

Assuming that these sorts of causes are not major factors, many people come out of depression with psychosocial interventions alone, ranging from informal ones (more friends, yoga practice, getting a dog, gratitude practice) to more formal ones (e.g., therapy, disputing negative thoughts routinely).

But for some people, psychosocial interventions alone are not enough; they also need to engage neurochemistry directly, taking steps ranging from supplementing tryptophan (perhaps as 5-HTP) to taking Zoloft. Of course, the side effects of medications need to be acknowledged: roughly a third or more of the people taking them find them ineffective or intolerable or both.

A common finding in research studies is that for moderate to severe depression, a combination of both psychosocial and medication interventions has the most benefit for many people. Psychosocial interventions have commonly the added benefit of reducing relapse into depression plus good “side effects” (e.g., feeling like you were the active agent of your own improved mood).

We also need to take into account what a person will actually do; for better or worse, it’s a fact that many people will not engage psychosocial interventions in a sustained way but they will take a pill each day.

Personally, I’m pragmatic and try not to get moralistic or dogmatic about any particular category of intervention.

Bottom-line, we are fundamentally a mind-body process, immaterial consciousness interdependently arising with material neurobiology – and I’ve found both mental and physical interventions to be very useful.

What’s going on in our brains in the experience of depression?

Depression affects both (1) the experiences we have and (2) our capacity to learn/grow/heal from them. So the practical implications are:

- Do sensible things to reduce depressive experiences, such as mental training (e.g., therapy, meditation, the Foundations of Well-being program), and physiological interventions (e.g., exercise, talking with licensed health professionals about the possibility of taking supplements such as 5-hydroxytryptophan or trying medication), and social support (really important!).

- When feeling depressed, let the experience be while also: observing its dynamic, changing, impermanent, “insubstantial” nature; and looking for what is also happening in your stream of consciousness, such as feeling loved or noticing something that is beautiful or pleasurable. In other words, don’t fight the depressive feelings, but don’t get drowned in them.

- When taking in positive experiences, compensate for the effects of depression on your brain’s capacity to change from positive experiences (#2 above) by focusing on and emphasizing their aspects of reward, surprise, delight, and embodied and active movement. This will help them “sink in” more.

- In general, to deal with #2 (above), get lots of exercise and have lots of complex and stimulating activities (this will help your hippocampus). Also try to include play in our list of activities (this will help your “neurotrophic factors”). These things should increase your brain’s neuroplastic response to your experiences, so it is more readily changeable for the better.

- Meanwhile, be someone who sometimes has depression, rather than being a “depressed person.” You are vast, you are fundamentally free!

Does the brain develop primarily due to the influence of relationships?

While the social dimension to life is profoundly important, it is just one of several major influences on the developing brain, especially past the first birthday. For example, the brain is incredibly shaped by a young child’s interior sensations, their engagement with sensorimotor experiences, and by their interior reflections (largely nonverbal) about their world and their self.

Can your techniques help people with autism or autism spectrum disorders?

I’m not a specialist in autism or neuro atypical people, but I have had a fair amount of experience with this territory. My classes etc. could be useful in building up psychological resources – like self-awareness, self-control, mindfulness, self-worth, calming, etc. – this would not directly address core spectrum issues but would be very helpful alongside them. Additionally, my classes, etc., might possibly be useful for core issues related to empathy, sensory flooding, and the internalization of the felt sense of being cared about.

Can you offer some insight or guidance on how I should pursue a career/graduate work/degree in neuroscience and psychology?

My own path has included a solid PhD in clinical psychology, and then a lot of self-study in neuroscience and contemplative practice, and then a fair amount of developing material at their intersection.

A key question to start with is whether you want an academic career or a clinical one, or a hybrid (hybrids are often the most fun). Or to put it very pragmatically, what sort of training is going to land you a tenure track appointment as an assistant professor somewhere you’d really like to work, or – alternately – give you the education and training that will enable you to pass the licensing exam as a psychologist (or neuropsychologist)? Or enable you to do both?

As to details, I actually know very little about the specifics of different programs. My intuitive encouragement is to aim high, and be willing to work hard for a few extra years: those costs will be amortized across the length of your career while the benefits of that extra work will compound exponentially. Sometimes it makes sense to do a mainstream program while building up your particular interests on the side. If you are an undergraduate looking to get into a graduate program, know that getting involved in research is critically important to being admitted to many graduate programs. So I’d look for any practical way to get involved in research opportunities at your college.

A key point if you are interested in preserving the option of a clinical practice: check the licensure requirements for the state(s) you want to be able to practice in, and make sure that your program will fulfill them. For example, many states are moving toward requiring American Psychological Association (APA) approval for PhD and PsyD programs that will count toward licensure.

Would you please suggest 2-3 simple practices to ``absorb the positive,`` which would be helpful to me at this early stage in my healing from stroke?

In terms of soothing and calming the alarms, there are happily many good things that can really help. They are all practical and simple, and you’ll see the results quickly:

- Do whatever you can to keep your physical body well-fed and well-slept. Try to avoid things that are inflammatory (a kind of alarm process in the immune system that is connected to the nervous system). Consider supplementing nutraceuticals such as GABA, tryptophan, and/or 5-hydroxytryptophan (talk with an experienced healthcare professional about this).

- Do some biofeedback with Heartmath’s Inner Balance device, to shift your resting state toward greater calm, and to recover faster from getting alarmed.

- A couple times a day or more, notice that you are basically alright right now. Really register this feeling, let it sink in. Whatever happened in the past and whatever the future holds, in the present you are basically OK.

- As you do your various practices, deliberately let go of any anxiety, any uneasiness, any defending against the next moment. Keep reminding yourself that you are strong and basically OK in the present. You can cope with challenges without getting worried or alarmed about it.

- Accept that sometimes you will feel alarmed. Don’t get alarmed…about getting alarmed. Try to regard the alert/alarm response as a kind of impersonal wave of experiences passing through awareness. Try not to identify with it; it’s there, yes, but kind of at arm’s length in your mind. You don’t have to move through your day afraid of getting triggered; if it happens, it will pass and you will remain.

- A few times a day, take one or two breaths to marinate in the sense of you caring about others, and others caring about you. This will be calming and supportive.

- Also a few times a day, look around and notice some of the many things that are working fine. Try to see the big picture, from a bird’s-eye view.

Additional Resources

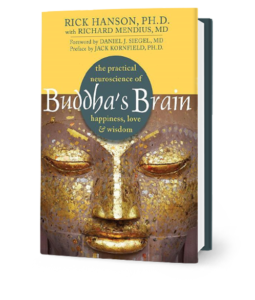

Buddha’s Brain by Rick Hanson, Ph.D.

Buddha’s Brain by Rick Hanson, Ph.D.